We are glad to present the interview from the bonus documentary in plain text form.

The Art of Personal Filmmaking

BC: My name is Bastian Clevé. I was born in Munich on January 1st, 1950. I received my artistic and filmic schooling both in Hamburg and at the San Francisco Art Institute. Since 1979, I have been living and working in Los Angeles. [until 1993]

Q: You have made over 30 experimental films. Is there a fundamental difference in approach to this manner of filmmaking?

BC: Yes. Basically, there are two distinct avenues by which I approach my own work. I may begin with an idea for a film without having a clear vision of what the resultant piece will look like. Thus, I explore the medium and test its limits as a means of articulating my own thoughts and the experience of making the film. In the film Echo, for example, I move and operate the camera very quickly, while journeying through a room to a landscape in order to obscure the identity of passing objects. In such filming situations, I do not know in advance what the character of the images will be.

In other instances, I am quite scientific in my approach. I begin with a theory or concept and accordingly apply those techniques appropriate to the creation of those previsualized images which fill my mind. If there is no known technique to produce the desired results, then I experiment and often build my own equipment in order to achieve my objective. This approach is often elaborate, laborious and slow. Pieces which involve single-frame printing are especially time consuming. The film Kaskaden is a product of this particular method: I began with a normal tilt up a tree; and later I manipulated the location footage through the use of an optical printer, employing a variety of possible techniques -slow motion, multiple exposures, colored filter changes, mirroring, manual movement of the filmstrip, etc. – to accomplish those images which were dwelling in my mind’s eye.

Q: You exhibit basic elements of the filmstrip itself, such as sprocket holes. Do you want to foreground the basic elements of filmmaking?

BC: Yes, and I use these elements of filmmaking in an alternative manner – not to reproduce reality, but to create a new, purely filmic reality. In the film Zenith, basic material aspects of the filmstrip function as ‘actors’. I try to create visual music and establish a sense of purity, that is why I left the film silent. There are, of course, other films in which I emphasize the materiality of film. In Empor, I was interested in the physical effect which is engendered at the very end of the film.

Q: Audiences expect to be shocked and challenged by experimental films. What is your position on this?

BC: I am not very interested in shocking the audience. I regard my films as a form of entertainment. Entertainment defined as an intellectual and sensitive form of stimulation. Despite the fact that Götterdämmerung created quite a controversy with its premiere at the Oberhausen Film Festival in 1974, I had intended only to create a film about the beauty of rhythm, dance and music. The film plays with the letters of the filmic alphabet, such as the interplay between a point of focus and a point of imperceptibility or the interplay between different focal lengths, the passage from a fade-in to a fade-out or the layering effect of a multiple-exposure.

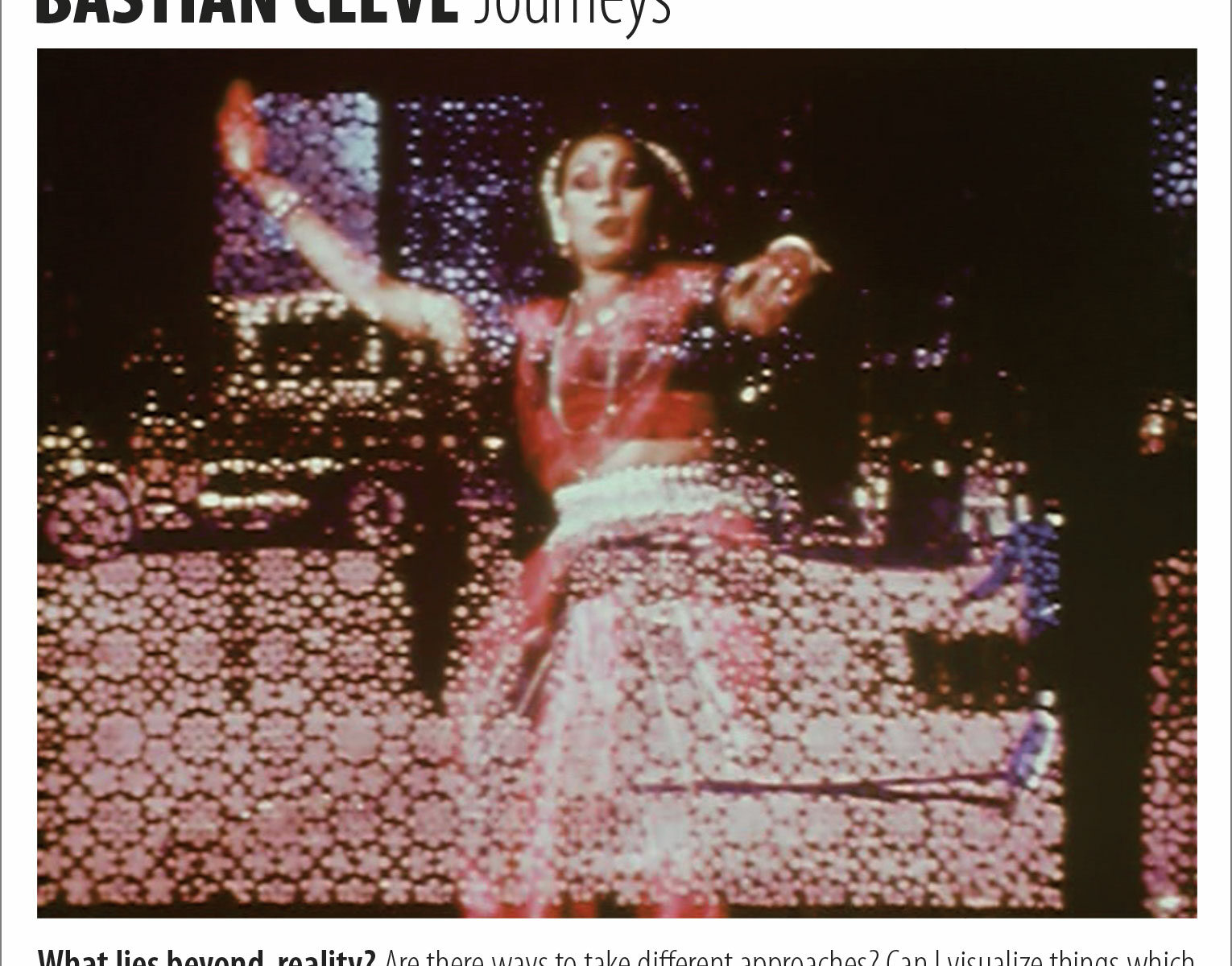

In the film Fatehpur Sikri ,I try to express my impressions of a journey through India and Nepal. The technique of the travelling matte allows me to combine images of a classical Indian dance and contemporary every- day life in India. The superimposed window of Fatehpur Sikri is placed between these two building block images. In a sense this brings me to another thought on the need of the filmmaker to discover those filmic techniques which will appropriately articulate a particular theme. In the case of Fatehpur Sikri, the technique used enhances and underlines the content of the images, the essence of their interchange and the governing idea which I wished to express.

Q: Most of your films are concerned with formal principles. Do you use any of these techniques to also tell a story, to narrate?

BC: Yes, I am currently moving in that direction. I am convinced that traditional stories can be told in a much more stimulating and dynamic way through the use and application of new visual methods and expressions. These [alternative devices] would allow the audience to be more imaginative itself. In fact, I attempt to create such a narrative in the feature-length film San Francisco Zephyr, which tells the story of a three-month journey through the United States and Canada. I use images from a rodeo, from Niagara Falls, from the Rocky Mountains and from a Fourth of July parade in San Francisco. The jazz musician, Eberhard Weber, created the soundtrack while watching the film. For him, the same principle of exploration and adventure governed his composition as it did for me -we both reacted to things which we had not seen before and created spontaneously.

Q: Why do you use simple and everyday images?

BC: Basically I am interested in creating images and films which I have not encountered previously. By using everyday images and subsequently transforming them into something beautiful and poetic, I can explore new aspects of reality – a reality which was previously perceived as a known factor by both myself and the spectator.

In addition, in Winterlandschaft I want to create a 3-D like effect in my work I accomplish this by using the color-negative filmstrip itself … that is as itself. Also, I place materials between the camera, projector and screen in order to achieve a spatial impression.

Q: Are there similarities between your work and the artistic methods and approaches apparent in other fields?

BC: Yes. I can understand that some of my work may be perceived as painting with light. I react to light as one reacts to music and thus compose with light. The process of filmmaking, for me, is similar to musical composition. I do everything by myself -beginning with the idea of the film, designing the lighting plan and executing the shoot, as well as the final edit. My works are, therefore, very personal.

The last film, Lichtblick, is like an optical poem; one of the objects – the Museum of Fine Arts in Hamburg – implies that artistic self-understanding resides within the context of the other arts. The musician, Klaus Schulze, composed the soundtrack for this film.